There are three major cultural and social factors that influence views on gender and sexuality: laws, religion and social norms.

Laws

In the United States and other Western countries cisgender women have greater legal protections than in other parts of the world. Globally, inequality is still enforced through laws in many parts of the world. For example, laws and policies prohibit women from equal access and ownership to land, property, and housing. Economic and social discrimination results in fewer life choices for women, rendering them vulnerable to poverty and human trafficking. Gender-based violence affects at least 30% of women globally. Some women who are victims of violence often have few legal protections or have limited legal recourse (United Nations Office of High Commissioner, 2018). For example, in some cultures, a woman may not be able to have her attacker arrested or prosecuted.

Within the United States there has been greater acceptance of homosexuality and gender questioning that has resulted in a rapid push for legal change. Laws such as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), both of which were enacted in the 1990s, have been met severe resistance and legal challenges on the grounds of being discriminatory toward sexual minority groups. Globally, a significant number of governments have recognized and legalized same-sex marriages. As of 2017, over 24 countries have enacted national laws allowing gays and lesbians to marry. These laws have mostly been enacted and enforced in Europe and North America. In Mexico, some jurisdictions allow same-sex couples to wed, while others do not (Pew, 2013).

Religion

Most religions have addressed the role for sexuality in human interactions. Different religions have different views of sexual morality. Most religions regulate sexual activity or assign normative values to certain sexual behaviors or thoughts through moral codes of conduct. Some religions distinguish between sexual activities that are practiced for biological reproduction (only allowed between males and females who are married) as moral and other activities practiced for sexual pleasure, as immoral. Sexual restriction is a universal of culture and typically defines incest and sex with animals as taboo or unacceptable behavior.

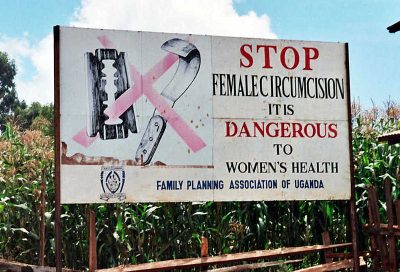

Female genital mutilation (FGM) includes procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. According to the World Health Organization (2018), FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women and reflects strongly held beliefs about inequality between the sexes. Female genital mutilation has no health benefits for girls or women. The practice predates religion and there are no religious texts that prescribe the practice; however, there are some religious leaders who believe the practice has religious support and encourage its continued practice.

Female genital mutilation is mostly concentrated in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, as well as locations with migrants from these areas including the United States. Female Genital Mutilation and is almost exclusively conducted on minors and is used as a way to regulate female sexuality and promote chastity. In cultures where FGM is practiced, a female who does not conform or submit to the procedure may be rejected by her community or find it difficult to find a mate and marry. Despite long held tradition and cultural norms ideas and beliefs about FGM are changing.

Norms

Cross-national research on sexual attitudes in industrialized nations reveals that normative standards differ across the world. For example, several studies have shown that Scandinavian students are more tolerant of premarital sex than are North American students (Grose, 2007). A study of 37 countries reported that non-Western societies like China, Iran, and India valued chastity highly in a potential mate, while Western European countries such as France, the Netherlands, and Sweden placed little value on prior sexual experiences (Buss, 1989).

For cultures that score high on Hofstede’s Masculinity/Femininity dimension there exists a sexual double standard which prohibits premarital sexual intercourse for women but promotes it for men (Hofstede, 2001; Reiss, 1960). This standard has evolved into allowing women to engage in premarital sex only within committed love relationships, but allowing men to engage in sexual relationships with as many partners as they wish without condition (Milhausen and Herold, 1999). As a result, a woman is likely to have fewer sexual partners in her lifetime than a man. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) the average 35-year-old woman has had three opposite-sex sexual partners while the average 35-year-old man has had twice as many (Centers for Disease Control, 2011).

Attitudes about sexuality can differ widely, even among Western cultures. For example, according to a 33,590-person survey across 24 countries, 89% of Swedes responded that there is nothing wrong with premarital sex, while only 42% of Irish responded this way. From the same study, 93% of Filipinos responded that sex before age 16 is always wrong or almost always wrong, while only 75% of Russians responded this way (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998). Sexual attitudes can also vary within a country. For instance, 45% of Spaniards responded that homosexuality is always wrong, while 42% responded that it is never wrong; only 13% responded somewhere in the middle (Widmer, Treas, and Newcomb, 1998).

Of industrialized nations, Sweden is thought to be the most liberal when it comes to attitudes about sex, including sexual practices and sexual openness. The country has very few regulations on sexual images in the media, and sex education, which starts around age six and is a compulsory part of Swedish school curricula. Sweden’s permissive approach to sex has helped the country avoid some of the major social problems associated with sex. For example, rates of teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease are among the world’s lowest (Grose, 2007). It would appear that Sweden, a culture low on the masculinity dimension, may be a model for the benefits of sexual freedom and frankness. However, implementing Swedish ideals and policies regarding sexuality in other, more politically conservative, nations would likely be met with resistance.

While in most Western, industrialized cultures like the United States exclusive heterosexuality is viewed as the sexual norm, there are cultures with different attitudes regarding homosexual behavior. In some instances, periods of exclusively homosexual behavior are socially prescribed as a part of normal development and maturation. For example, in parts of New Guinea, young boys are expected to engage in sexual behavior with other boys for a given period of time because it is believed that doing so is necessary for these boys to become men (Baldwin & Baldwin, 1989).

Kosofsky Sedgwick (1985) described nonsexual same-sex relationships along a continuum which she termed homosocial. Women enjoy more fluidity along the continuum than males in Western cultures, specifically North America. For example, females can express homosocial feelings through hugging, hand-holding, and physical closeness. In contrast, males refrain from these behaviors since they violate heterosexual norms for males. Women have more flexibility and can express more behavior variations along the heterosocial-homosocial spectrum but male behavior is subject to strong social sanction if it veers into what is considered homosocial.