Culture shock and the stages of culture shock are part of the acculturation process. Scholars in different disciplines have developed more than 100 different theories of acculturation (Rudiman, 2003); however contemporary research has primarily focused on different strategies and how acculturation affects individuals, as well as interventions to make the process easier (Berry, 1992).

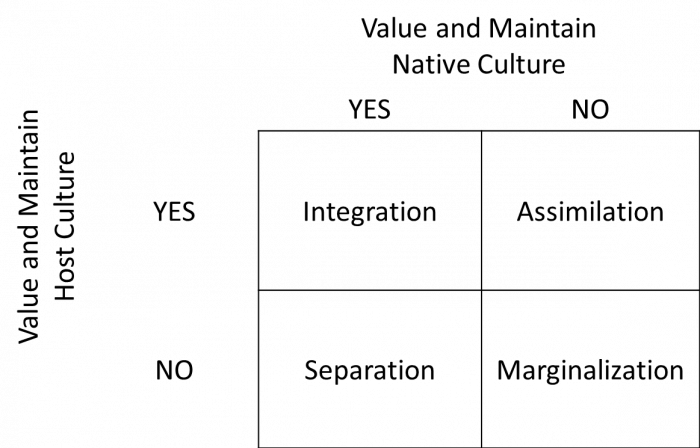

Berry proposed a model of acculturation that categorizes individual adaptation strategies along two dimensions (Berry, 1992). The first dimension concerns the retention or rejection of an individual’s native culture (i.e. “Is it considered to be of value to maintain one’s identity and characteristics?”). The second dimension concerns the adoption or rejection of the host culture. (“Is it considered to be of value to maintain relationships with the larger society?”) From these two questions four acculturation strategies emerge:

- Assimilation occurs when individuals adopt the cultural norms of a dominant or host culture, over their original culture.

- Separation occurs when individuals reject the dominant or host culture in favor of preserving their culture of origin. Separation is often facilitated by immigration to ethnic enclaves.

- Integration occurs when individuals are able to adopt the cultural norms of the dominant or host culture while maintaining their culture of origin. Integration leads to, and is often synonymous with biculturalism.

- Marginalization occurs when individuals reject both their culture of origin and the dominant host culture.

Studies suggest that the acculturation strategy people use can differ between their private and public areas of life (Arends-Tóth, & van de Vijver, 2004). For instance, an individual may reject the values and norms of the host culture in his private life (separation) but he might adapt to the host culture in public parts of his life (i.e., integration or assimilation). Moreover, attitudes towards acculturation and the different acculturation strategies available have not been consistent over time. For example, for most of American history, policies and attitudes have been based around established ethnic hierarchies with an expectation of one-way assimilation for predominantly white European immigrants (Fredrickson, 1999).

Studies suggest that the acculturation strategy people use can differ between their private and public areas of life (Arends-Tóth, & van de Vijver, 2004). For instance, an individual may reject the values and norms of the host culture in his private life (separation) but he might adapt to the host culture in public parts of his life (i.e., integration or assimilation). Moreover, attitudes towards acculturation and the different acculturation strategies available have not been consistent over time. For example, for most of American history, policies and attitudes have been based around established ethnic hierarchies with an expectation of one-way assimilation for predominantly white European immigrants (Fredrickson, 1999).

The metaphor of the melting pot has been used to describe the immigration history of the United States but it doesn’t capture the experiences of many immigrant groups (Allen, 2011). Generally, immigrant groups who were white, or light skinned, and spoke English were better able to assimilate but immigrant groups that we might think of as white today were not always considered white enough. For example, Irish and Italian immigrants were discriminated against and even portrayed as black in cartoons that appeared in newspapers and it wasn’t until 1952 that Asian immigrants were allowed to become citizens of the United States (Allen, 2011).

Within the United States, separation as an acculturation strategy can still be seen today in some religious communities such as the Amish and the Hutterites. An integration strategy for acculturation can be observed within Deaf culture. Individuals who are deaf use a different language to communicate, learn about their culture and language from institutions and not their family (most deaf children have hearing parents) and are united by shared experiences as persons with disabilities. Deaf individuals in the United States live within the dominant culture and share the same cultural values but are separated by language and disability (Maxwell-McCaw, et al., 2000). Members of the Deaf culture have created their own unique cultural and social norms for communicating, interacting and experiencing the world around them.

Some acculturation research suggests that the integrated acculturation strategy has the most favorable psychological outcomes (Nguyuen, et al., 2007; Okasaki, et al., 2009) for individuals adjusting to a host culture and marginalization has the least favorable outcomes (Berry, et al., 2006). Additionally, marginalization has been described as a maladaptive acculturation and coping strategy (Knust et al., 2013). Other researchers have argued that the four strategies have very little predictive validity because people do not always fall neatly into the four categories (Kunst et al., 2013; Schwartz et al., 2010). Situational determinants (e.g., traveling with family, familiarity with language) and environment factors also impact the availability, advantage, and selection of different acculturation strategies (Zhou, 1997).