1

Learning Objectives

In this chapter we will look more closely at a view of politics through institutions. In doing so, we will clarify a key divide in the discipline of political science.

The traditional approach to the study of political science was both normative and institutionally focused. This approach would, for example, consider the best arrangements for legislative, executive, and judicial powers of government. This view of politics is very old in Western political theory, at least as far back as the Ancient Greeks. Plato and Aristotle were both normative philosophers in the sense that they were concerned with what forms of government best achieved justice. This normative and institutional view generally dominated politics for centuries. What are the advantages of a republican form of divided government? What best brings security to a political community: democracy or more authoritarian rule? What sorts of disadvantages come from a judiciary with the power to strike down legislative law? These are all questions that come from a traditional view of politics that is institutional and normative.

Beginning in the 1930s, however, the discipline experiences a behavioralist revolution that emerged in American academia in particular. This revolution sought to explain politics in a very different way—by using objective quantitative data to explain political behavior. One of the goals of this change was to make the study of politics more scientific. Or, in other words, behavioralists sought to rigorously update the discipline using scientific methods to understand why individuals behave certain ways when it comes to political belief and action. In the sense that a scientific approach seeks objectivity—what is as opposed to what ought to be—it is clear that this is a major turn from the more normative understanding of politics in the past. Likewise, this new turn in the study of politics focuses on the behavior of individuals or groups, not on the structure of institutions or forms of government.

Exercise 3.1

Reflect for a moment on what kind of political science work you are most interested in—normative or objective? Political behavior or political institutions?

Let’s take an example: how do democracies emerge out of non-democratic political communities? Answering such a question may take a behavioralist approach, focusing on actors, such as democratic activists or social movements, politicians or bureaucrats. Or it may take an institutional focus, such as looking at the structures of government or economic systems conducive to democratic development. There is clearly an objective approach to answering this question—simply explaining when democracies arise out of non-democracies—but it may also have a normative component to it: how should democracy develop out of non-democratic political communities?

Since the behavioralist turn in the 20th century, there have been a few more significant turns in the discipline of political science. One, emerging in the 1970s and 80s, is new institutionalism, which uses a variety of methodological approaches to understanding how norms, rules, cultures, and structures constrain and influence individuals within a political institution. The new institutionalist approach brings together the traditionally institutional view of politics and the behavioralist view of politics: how do institutions effect individual behavior?[1] Before we go any further, we should think about what we mean by an “institution.” An institution is a set of rules and practices that are relatively durable—individuals may come and go, but the rules and practices themselves endure over longer periods of time. These rules and practices are often coherently tied together as a system of meaning—the institution generally has a purpose out of which rules and practices are established to logically realize that purpose. In this view, institutions are fundamentally about constraining individual behavior—institutions, in other words, should not simply be some aggregation of individual behaviors. Institutions should instead be resilient in the face of idiosyncratic preferences of individuals or changing circumstances external to that institution.

Three Forms of New Institutionalism

New institutionalism seeks to understand how two or more institutions interact with one another or how individuals interact with and within institutions. There are three broad forms of new institutionalism we will consider here: rational choice institutionalism, sociological institutionalism, and historical institutionalism.

Rational choice institutionalism is the most mathematically rigorous form of new institutionalism, and seeks to explain how a system of rules and incentives in an institution are contested and used by individuals within that institution. Borrowing from economics and organizational theory, rational choice institutionalism uses modeling and game theory to test assumptions about how individuals will interact with rules and incentives. Let’s clarify what we mean by rational choice. Rational choice theory has several core assumptions: actors are rational; actors know their preferences and can define them; actors are aware of available information, probabilities of events, and potential costs and benefits associated with their preferences; actors thus take those preferences and make the best possible choice they can given the constraints they face; and, lastly, actors will act consistently in making the best possible choice at a given time. Rational choice theory is not just about isolated individual behavior, however. A basic assumption of rational choice theory is that aggregate social systems, rules, procedures, and behaviors are derived from the behavior of individual actors. In other words, rational choice institutionalism can explain certain phenomena or characteristics of an institution, but that explanation comes from examining individual behavior within that institution.

Generally speaking, rational choice institutionalism focuses on one institution (as opposed to multiple institutions) and at one point in time (as opposed to how an institution develops over time). In the preceding chapters, we have touched upon this rational choice view in a number of ways: in Chapter One, we considered the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a game in which individuals are pitted against one another in order to maximize their potential advantages. The rules of this game (a pre-determined number of years in prison among four potential avenues of cooperation or defection) can be regarded as an institution that constrain individuals and compel them to make decisions. Also in Chapter One, we considered the perspective of politics as a field in which power is contested among individuals. In this view, the field itself, with its inherent rules and constrains on where power flows, can be regarded as an institution in which individuals contest for that power. Before moving on to the other two forms of new institutionalism, reflect for a moment on the advantages and disadvantages of this approach to the study of politics. One advantage may be that this approach can more precisely predict political outcomes, since it very often confines the analytic focus to a single institution at a single moment in time. With this argument, however, a potential disadvantage becomes clear: rational choice institutionalism may miss external factors outside the institution in focus that are influencing a given outcome. Moreover, rational choice institutionalism’s more ahistorical approach may miss crucial developmental factors, emerging over time, that influence a given outcome.

Sociological institutionalism generally rejects the assumption that an institution’s rules, constraints and procedures are inherently rational or tied to efficiency, and instead emphasize the ways in which institutions develop through culture—perhaps through tradition, myth, or ritual—and are thus culturally constructed. Symbolic, ceremonial, or moral characteristics often determine the structure of institutions in this view, not rational choices of maximizing incentives, benefits, or efficiency. If we define culture to broadly encompass collective human expression and shared ways of life from a particular nation, people, or social group, rules and constraints of political institutions are in fact a part of culture. Consider for example the prohibition of alcohol in early 20th century America. This was much of a cultural as it was a political movement—moral outrage over the evils of liquor and the saloon were widely expressed in popular culture at the time, in movies, literature, vaudeville. This moral and cultural movement changed America’s political institutions directly with varying prohibition laws at the state and local level and eventually culminating in a change to the US Constitution. Constitutional prohibition was widely seen as a social policy failure—indeed, the 18th Amendment remains the only constitutional change overturned by a subsequent amendment (the 21st).

Historical institutionalism, as the name suggests, emphasizes institutional change over time, focusing on the ways in which the development of institutional rules and constraints influence individuals. For an example, let’s consider the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment, which protects individuals from government depriving them of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This Amendment, drafted after Union victory over the Confederate States of America, sought to guarantee basic civil liberties for all people. Over time, certain economic interests sought to use this law in order to protect themselves against government regulation of businesses practices. The so-called Lochner Era—so named after a case in which the Supreme Court struck down a New York state law that limited working hours for bakers—was characterized by courts evoking the 14th Amendment to strike down economic regulation passed by state and federal legislatures. This was a pre-New Deal Era of American law and politics (roughly 1897 to 1937), in which courts frequently stopped progressive economic legislation. The Lochner Era’s use of the 14th Amendment is often regarded as an interpretation far afield from the original intentions of its drafters, the 39th Congress in 1866, who clearly intended the amendment to be a response to the end of slavery and provide government protections for newly freed slaves. We can understand this Lochner Era through the lens of historical institutionalism—the meaning of the 14th Amendment changed over time and provided new ways for certain interests, namely economic, to influence government and achieve their political aims.

Traditionally, political science as a discipline was more normative and institution-focused. The behavioral revolution in the 20th century sought to make political science more scientific. With the use of quantitative analysis, political behavior could be studied more objectively. Institutions were not ignored entirely but very often seen as the sum of aggregate political behavior. The return of institutionalism—new institutionalism—created a more hybrid disciplinary focus on the relationship between individuals and institutions and between institutions themselves. For the rest of this chapter, we will take a broad look at a number of institutional systems of government, beginning with the distinction between unitary states and federated state and then overview the legislative, executive, and judicial foundations of modern government.

Unitary vs Federal States

A unitary state is one in which a central government has the ultimate authority to govern. There may be local or regional sub-units of government in a unitary system, but their powers are delegated by the central government that can also create or abolish these sub-units. In comparing unitary states to other unitary states, there is exists a significant amount of variation. Some countries have a decentralized unitary state in which a fairly large degree of power is delegated to local sub-units that do much of the governing. This is often referred to as a devolution of powers to local government and takes place by statute (written law passed by a legislature). This is still a unitary state because the central government has the absolute authority to abrogate, limit, or expand those powers. An example is the United Kingdom, in which Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have some autonomous, devolved power, but this power is delegated by the British Parliament. England has no devolved power—it is governed directly by the British Parliament. In other words, the country of England, which is part of the United Kingdom, has no government of its own, unlike Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Many unitary states are centralized and either have no administrative sub-units or, if they do, those sub-units do not have the authority to make their own laws. Ireland, Portugal, and Romania are examples of centralized unitary states.

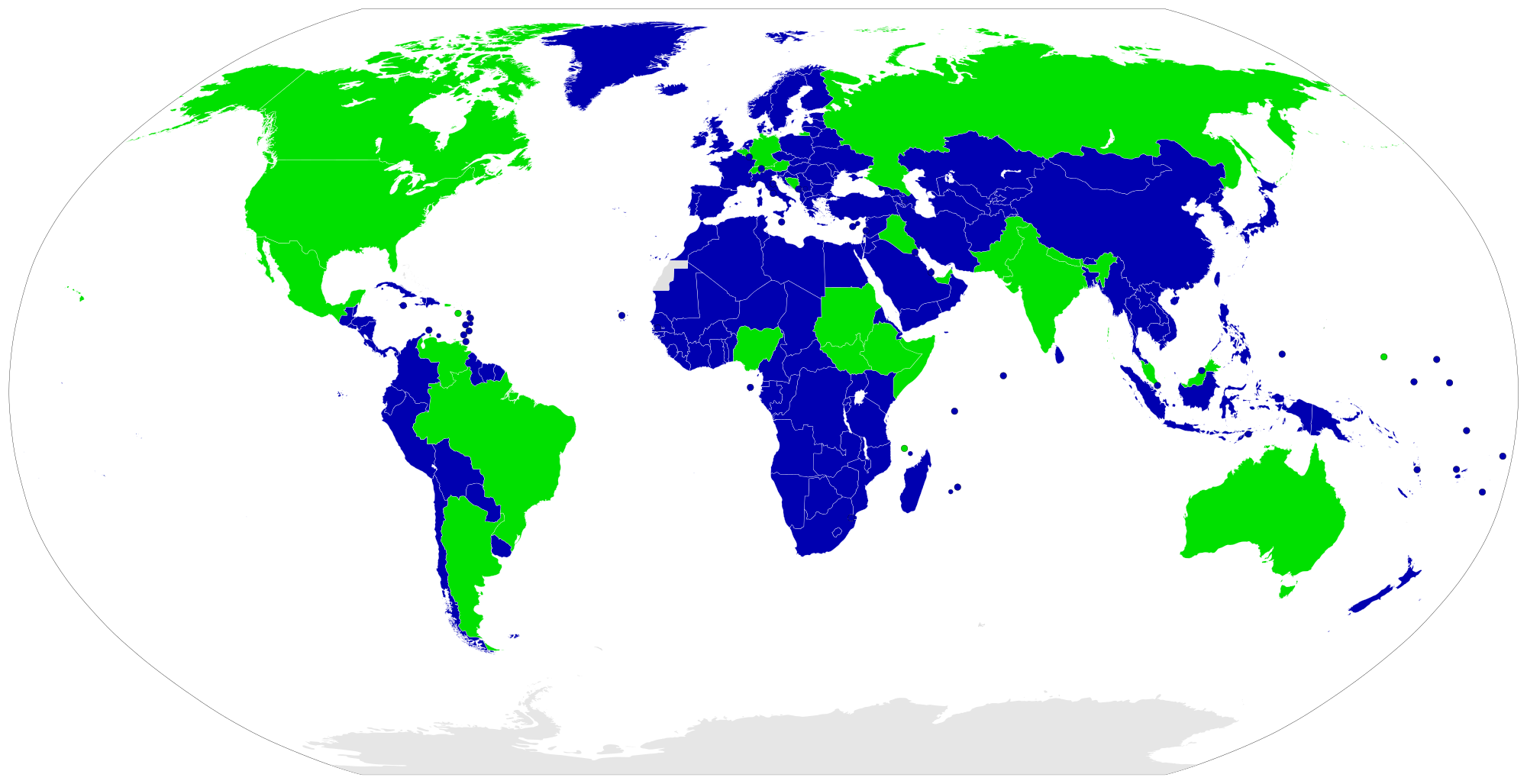

The vast majority of the world’s states have a unitary system of government. Of the 193 member states of the United Nations, 165 of them have unitary systems of government. Why is a unitary system such a common system of government? What are its advantages? First of all, countries that are small and have relatively homogenous populations—and are therefore, on the whole, easier to administrate and govern—almost always have unitary states. One advantage of a unitary state is that it may make governing and administration more efficient. Centralization of power often leads to fewer overlapping lines of authority, fewer institutions of governance, and stakeholders who share a common mission and authority. This is true in theory but in practice, of course, things can get complicated. For instance, if a unitary state is a system of government for a country with large minority populations spread over a sizable geographic area, centralized political control could weaken the legitimation of that political authority, and could in turn make it harder for the government to deliver goods and services, maintain stability, or effectively govern.

Federalism is a system of government in which sub-units (states, provinces, etc) are partially self-governing and are bound together by a constitution and a central federal government. The self-governing status of the sub-units, and the arrangement of power shared between these sub-units and the federal government, cannot typically be unilaterally changed. These power arrangements can instead only be altered with the consent of both the federal government and the sub-units. Constitutions in a federal state serve to formalize the arrangement of power between the federal government and sub-units. In a sense, these sub-units enjoy a degree of sovereignty, although without international recognition and often without any powers to conduct foreign policy. The sub-units are typically equal in their powers, although in asymmetric federalism, some sub-units have more power than others, as is the case with Malaysia.

Most federal states are large countries with multiethnic populations. Seven out of the eight largest countries in the world are federations—India, United States, Brazil, Russia, Pakistan, Mexico, and Germany. Of the 27 federal states in the world, only the Comoros, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Micronesia may be said to be smaller, relatively homogenous countries. Comoros is an African nation of three islands in the Indian Ocean. A federal presidential republic, the three islands of Comoros have a high degree of autonomy from one another, with their own constitutions, presidents, and parliaments, but are bound together by a federal constitution and a power sharing agreement in which the federal president rotates among the three islands. Similar to Comoros, Saint Kitts and Nevis is a federation of the two islands and Micronesia is a federation of several distantly scattered islands. The central European country of Austria is also a relatively small and homogenous federation. Austria became a federation in 1918 followed the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in WWI and the subsequent adoption of a constitution.

As with unitary systems of government, there is a lot of variation within federal systems. The key to evaluating federal systems is determining the degree of political centralization and whether or not political authority in sub-units can be limited, determined, or abolished by the centralized federal government. For example, in the United States of America the relationship between the states and the federal government is codified in the U.S. Constitution. State and local governments in the U.S. have wide authority to pass laws and regulations they deem necessary, while the federal government has more expressed limitations. While the Constitution states that the federal government guarantees a republican form of government in the states, it cannot abolish states or determine the makeup of their political institutions. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, can strike down any state law, an important federal power over the states. There is a significant amount of variation that exists between states in America—capital punishment, gun regulation, taxation, education spending, and healthcare are among the issues that can have very different policy approaches at the state level.

One advantage of a federal system is that it can better represent regional interests and minority groups within a country since political authority is shared among a central government and regional governments, but this is not always the case. Take, for example, the Civil Rights era in 20th century America. Southern states generally fought to preserve segregation and racial inequality and pointed to their state political authority granted by federalism as justification. Through federal courts, executive action, and ultimately congressional legislation, the federal government stepped in to pressure the South to abandon segregation. Following the Brown v Board of Education Supreme Court decision, which found racial segregation unconstitutional, schools across America began a slow process of integration. In September 1957, the Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus resisted the integration citing imminent violence and riots (without any evidence) and instructed the Arkansas National Guard to turn away black students trying to attend their first day of school in Little Rock’s Central High. President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded by federalizing the Arkansas National Guard and ordering them to do the exact opposite—ensure the safety of the students and their admittance into the school.

On the surface, the distinction between federal and unitary systems of government seems clear enough, but this belies a great deal of complexity. While unitary systems tend to emphasize efficiency of government over representation and federal systems emphasize representation over efficiency, there are a number of other variables that can make unitary systems inefficient and federal systems unrepresentative. For the remainder of this chapter, let’s consider legislative, executive, and judicial power and how these powers are manifested in political institutions.

The Law Makers

Legislative power is the power to make law. This power is vested in a legislature, which may also be called a congress, assembly, council, or parliament, and is composed of legislators whose main tasks are to draft and vote on legislation with the aim of turning it into law. Legislators may also have other important duties, such as determining and authorizing a government’s budget, providing oversight on other branches or institutions of government, and confirming governmental appointments. In representative democracies, legislators are usually voted into office, either through popular or indirect elections, although in some cases they may be appointed by another branch or institution of government (this was the case in the United States Senate, whose members were appointed by state legislatures until the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913). In popular elections, representatives are voted into office directly by the people. In indirect elections, voters typically vote for people who will then choose the representatives (the process for selecting the US president, the Electoral College, is an example of an indirect election).

A unicameral legislature means there is only one unit—or institution—for law making. A bicameral legislature is composed of two institutions. Take, for example, the two main legislative bodies of Germany—the Bundestag and Bundesrat. The Bundestag is the larger, popularly elected chamber of the German legislature. Members of Bundesrat, the smaller chamber that represents the sixteen federated states of Germany, are delegated seats by the German state governments. In effect, the Bundesrat is a legislative chamber that gives direct state representation in national government. This is similar to the United States Senate before the passage of the 17th Amendment, in which each state legislature appointed both senators from that state. What are the advantages of a bicameral legislature? Stability is often considered a key advantage. For the framers of the US Constitution, for example, one of the aims of the United States Senate was to provide some stability to law making in government—senators serve 6 year terms (as opposed to 2 year terms in the House of Representatives) and elections for senate seats are staggered over time so that only one third of senate seats are up for election every two years.

Another advantage of a bicameral legislature is that it can provide higher quality legislation. The theory here is that by having to pass through two legislative bodies, legislation can be refined and improved upon. In the United States Congress, bills that pass the House of Representatives are sent to the Senate for review. The Senate may change, amend, or otherwise refine this bill and send it back to the House for another vote. In this way, legislation has the opportunity to be improved upon and debated. It also gives the opportunity for the public to debate and voice their opinion on legislation as it is shaped within and between both chambers of Congress. A third advantage may be more varied representation. In Germany, the Bundestag represents the German people directly, whereas the Bundesrat better represents the interests of the German state governments. In the United States, members of the House of Representatives are elected by districts, geographical areas within states, roughly equal in population, the boundaries of which are drawn by state legislatures. The US Senate is determined by statewide elections, with 2 seats per state regardless of the state’s population. The interests of people in a district may be very different than the interests of the state as a whole. Take California as an example: in statewide elections, it consistently votes for liberal Democrats, but there are a number of very conservative areas in the state, and district-based elections in the House give those conservative voters better representation.

The size of a legislature varies from one government to another, and in considering the size (or number of legislators) there is an important tradeoff between efficiency and representation. Large legislatures reflect greater representation of the people in government, since there are more representatives per population. On the other hand, a smaller ratio of representatives per person may help make the passage of law more efficient and easier. Let’s use a hypothetical example. The country of Sneetchland has 10 million people. Roughly 70% of the population, or 7 million people, are members of the ethnic majority, the Star-Bellied Sneetches, who are concentrated in geographically smaller urban areas in the south of the country. The remaining population belong to the ethnic minority, Sneetches Without Stars, who are more sparsely populated over a large mountainous region in the north of the country. What do you think is the ideal legislature for Sneetchland? Determine whether Sneetchland will have a unicameral or bicameral legislature, whether representatives are chosen by direct elections, indirect elections, or appointment by some other political institution, and how many representatives their should be (determine the number in both chambers if bicameral).

Exercise 3.2

Reflect on your choices and consider what outcomes you may get from how you structure a legislature. We will discuss your decisions and consequences in class.

The Law Givers

Executive power is the power to implement, execute, and enforce law. In a separation of powers model, this power is distinct from making law (legislative power) or interpreting law (judicial power). Those who hold executive power are the givers of law—they make law real, bringing it out of the halls of government and into the everyday society. Executive law is bureaucratic, it is police power, it is regulatory power, it is military power. In American politics, the law givers are the mayors of our towns and cities, the governors of our states, and the president of the United States. Reflect for a moment on what it means to implement law. What does this look like? How does one implement law? As we shall see in the section on bureaucracy below, much of government is dedicated to this function.

An initial distinction should be made between a head of state and a head of government. A head of state is a representative of national unity—a monarch, supreme leader, or president who is the chief leader of a nation. This role is largely ceremonial with little specific duties or powers within the government. In some countries the head of state oversees formal ceremonies, transfers of power, or recognition of laws passed by a legislature. If we consider a nation to be, in the words of Benedict Anderson, “imagined communities,” the head of state is a symbolic representative of a shared national identity. A head of government is the chief executive responsible for the governance of the state holding executive power to oversee the implementation and enforcement of law. The head of state and head of government indicate the difference between a state and a government. A state, or country, is a political community bound together by a single system or type of government. A government, on the other hand, is a group of individuals who are authorized (such as through elections) to govern a state or country for a period of time. In other words, a state is much more permanent than a government. Governments come and go; a state is a durable system that includes numerous governments over time.

In a presidential system, a president holds both the roles of head of state and head of government. The American president, for example, must be both a unifier of the nation and carry the chief executive functions of government. As head of state, the U.S. president receives foreign dignitaries, addresses the nation regarding major events or crises, and travels abroad as the chief representative of the United States. As head of government, the U.S. president is responsible for directing his or her cabinet in the implementation, execution, and enforcement of law, and is head of the vast bureaucracy of various departments and agencies that see to the day-to-day work of executing laws passed by Congress. In this sense, the American president is both the leader of the nation and the leader of executive government.

In a parliamentary system, the roles of head of state and head of government are generally distinct from one another. The system of government in the United Kingdom, for example, is known as the Westminster political system, in which the head of government is the prime minister who is also a member of parliament. In this sense, the separation of powers is blurred—ministers of the executive have important roles in both the making and execution of law. The head of state in a parliamentary system is typically a monarch or president, fulfilling the functions of representing national unity and identity. The Central European country of Hungary, for example, is a unitary parliamentary republic with a unicameral legislature (the National Assembly), a Prime Minister who is elected by the legislature and serves as the head of government, exercising executive powers. The President of Hungary is also elected by the National Assembly, but serves as the head of state, performing the ceremonial functions and also serving as Commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

The Law Adjudicators

Courts around the world have developed over centuries as a legal decision making authority. The mediation of conflicts and disputes, the final word on the law, a political authority that gives individuals remedy and relief, the decision on what law applies to a particular matter (the application of law), all these actions involve legal decision making. The legal process involves the rules, functions, institutions, and actors in this realm of judging the law. Courts are the main institution in which this process takes place. There are generally lower, intermediate, and higher courts in a judicial system. Courts operate through the power of jurisdiction—the practical authority to speak on the law. There are several types of jurisdictions: personal, subject-matter, and territorial jurisdiction, and original vs appellate jurisdiction. Personal jurisdiction grants a court an authority over the parties involved in a dispute. Under personal jurisdiction, a court has authority to hear matters of law and facts of the case and can enforce a decision on the parties involved in a suit. Subject-matter jurisdiction pertains to a type or subject of law: probate courts decide questions pertaining to wills or the administration of estates, family courts deal with divorce and child custody matters, etc. Territorial jurisdiction grants a court the authority to render judgement in a particular geographic area. For a court to render a judgement, it must have a combination of subject and either personal or territorial jurisdiction.

A distinction can also be made between original and appellate jurisdiction. Original jurisdiction grants a court the authority to hear a case for the first time—no other court or legal authority has rendered judgement of the case. An appellate jurisdiction is the legal authority to hear an appeal of a prior decision. Appellate courts are appeals courts—they are generally regarded as higher authorities on the questions of law and are presided over by more prestigious judges who review the findings of law in lower courts. Here it is useful to think about the difference between questions of fact and questions of law. Questions of fact (or point of fact) are answered with evidence from particular circumstances or factual situations, such as was the gun in the right hand or the left hand when the crime was committed, was the defendant driving at 70 miles per hour or 50 miles per hour, etc. Questions of law are answered by applying legal principles to the details of a case: did the presence of a gun in the dispute reach the legal definition of menacing? Does the speed of 70 miles an hour in this incident constitute reckless behavior? This distinction between questions of fact and questions of law help us understand the distinction between original and appellate jurisdiction: in original jurisdiction, questions of fact must be scrutinized and settled in order to answer the questions of law; in appellate jurisdiction, those questions of fact have been settled and an appellate judge need only consider the questions of law and how they were answered by the lower court or courts.

Let’s take the example of the Kansas judicial system in the U.S. state of Kansas, which is governed and determined by the Kansas State Constitution. At the lowest level, Kansas has municipal or city courts that have original jurisdiction over alleged violations of that city’s ordinances, such as a traffic violation. There are no juries, only judges, and there are no appellate courts at this level. The jurisdiction is territorial (within the city limits) and subject specific (violations of city ordinances). The Kansas district courts have general original jurisdiction over all civil and criminal matters, everything from small claims to murder. Civil and criminal jury trials that are held at this level. There are 31 judicial districts across Kansas, most of which cover more than one county (although all 105 counties in Kansas have an actual district court to conduct proceedings). The Kansas district courts also have an appellate jurisdiction—they hear all appeals from the municipal courts below. The Kansas Court of Appeals is the intermediate appellate court that has personal jurisdiction to hear all appeals from the lower district courts and also appeals from the Kansas State Corporation Commission, a 3-member board appointed by the governor whose mission is to protect environmental resources and rights to shared resources such as water, transportation, or energy. Although its administrative functions are located in the capital Topeka, the Court of Appeals can sit anywhere in the state. Lastly, the Kansas Supreme Court is the court of last resort in the state judicial system. It can hear appeals directly from district courts in serious criminal matters, reviews cases in the Court of Appeals, and may transfer particular cases from the Court of Appeals to its jurisdiction. The Kansas Supreme Court also hears all cases in which a statute has been held unconstitutional and has original jurisdiction in some types of cases. In Chapter 4, we will look in more detail at public law, the law that governs relationships between individuals and the government.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we got a better sense of the discipline of political science and how it provides behavioral and institutional explanations to political phenomena we observe in the world. We then looked at a number of political systems and institutions, broadly conceived. The difference between federal and unity systems of government suggests a trade off between efficiency and representation—in theory, unitary systems of government may be more efficient, whereas federal systems may better represent regional interests and minority groups. In practice, this is of course not always the case, and so a deeper analysis of the characteristics of federal and unitary systems is necessary in order to evaluate systems of government in terms of efficiency and representation.

In looking at legislative powers, there may also be a trade off between efficiency and representation when determining the number of representatives in a legislature—a large number of representatives per population may give greater representation but at the expense of efficiency, whereas a smaller number of representatives per population may enhance efficiency at the expense of representation.

Executive power is the power to implement and enforce law. Institutionally, this executive power is operates through a bureaucracy that administers the state, implements law, and wields regulatory power. The head of this institutional administration and execution of law is either a president or prime minister, who oversees executive action and often serves as head of the military forces. In a presidential system, the president is typically both head of government and head of state.

Judicial power is generally institutionalized in a system of courts that make decisions on legal matters. In a federal system, there typically state and federal courts that remain distinct from one another in important ways. Courts operate with the authority of jurisdiction and there are five important types of jurisdictions: personal, subject-matter, territorial, original, and appellate, that often overlap and are simultaneously in effect.

We may think of the process of law making, law giving, and law judging as a temporal process that is chronological—law is initially made, it is then implemented, and finally it is adjudicated. This may be helpful, but a chronological view of law making, law giving, and law adjudicating belies the complexity and dynamic that exists between these powers and the institutions that wield them. Executive power can influence the making of law in a number of ways (like the pocket veto or agenda setting power of an American president, for example), and judicial power and its decision making authority can often compel legislatures to make new laws as a response to legal decision making.

In the next chapter, we will take a closer look at public law and the ways in which law structures and shapes politics.

Media Attributions

- 2000px-Map_of_unitary_and_federal_states.svg

- 1024px-Deutscher_Bundestag_Plenarsaal_Seitenansicht

- David Brian Robertson, "The Return of History and the New Institutionalism in American Political Science." Social Science History, vol. 17, no. 1 (Spring 1993): pp. 1–36 ↵

Written law passed by a legislature.

The authority to make legal judgements and decisions. Jurisdiction is derived from the Latin jus (law) and dictio (saying) and means literally "to speak on the law."