13

The Ray Aspect of Light

Instructor’s Note

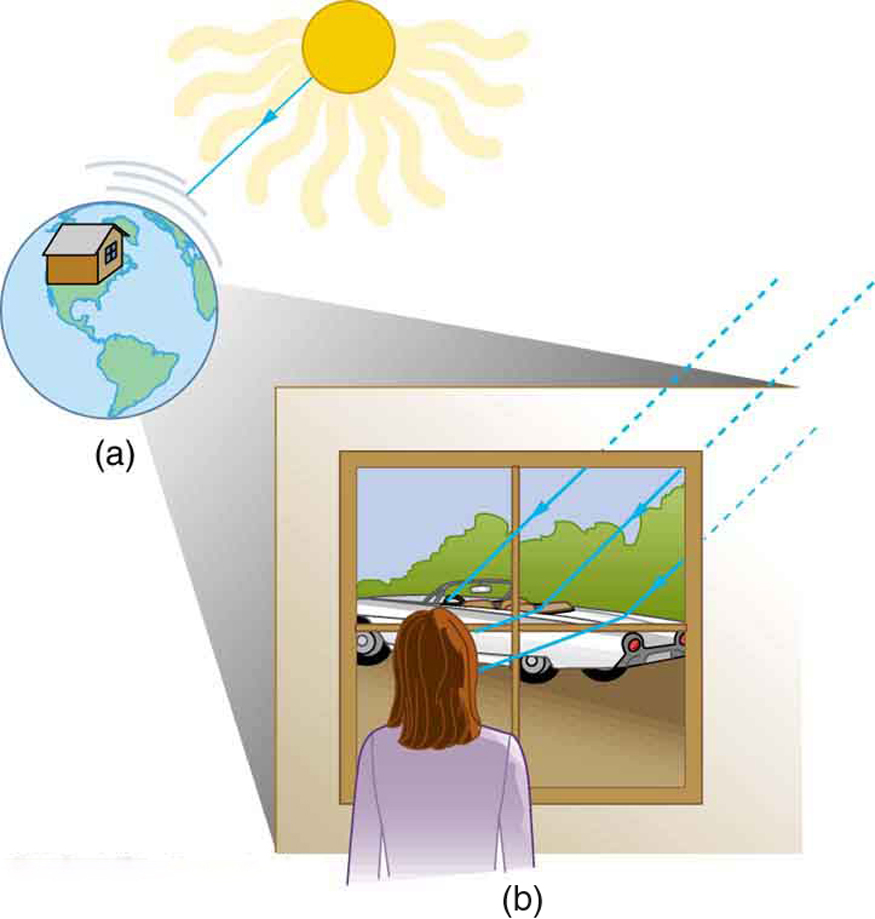

There are three ways in which light can travel from a source to another location. (See Figure 1.) It can come directly from the source through empty space, such as from the Sun to Earth. Or light can travel through various media, such as air and glass, to the person. Light can also arrive after being reflected, such as by a mirror. In all of these cases, light is modeled as traveling in straight lines called rays. Light may change direction when it encounters objects (such as a mirror) or in passing from one material to another (such as in passing from air to glass), but it then continues in a straight line or as a ray. The word ray comes from mathematics and here means a straight line that originates at some point. It is acceptable to visualize light rays as laser rays (or even science fiction depictions of ray guns).

Experiments, as well as our own experiences, show that when light interacts with objects several times as large as its wavelength, it travels in straight lines and acts like a ray. Its wave characteristics are not pronounced in such situations. Since the wavelength of light is less than a micron (a micrometer μm or a thousandth of a millimeter), it acts like a ray in the many common situations in which it encounters objects larger than a micron. For example, when light encounters anything we can observe with unaided eyes, such as a mirror, it acts like a ray, with only subtle wave characteristics. We will concentrate on the ray characteristics in this chapter. Since light moves in straight lines, changing directions when it interacts with materials, it is described by geometry and simple trigonometry. This part of optics, where the ray aspect of light dominates, is therefore called geometric optics. There are two laws that govern how light changes direction when it interacts with matter. These are the law of reflection, for situations in which light bounces off matter, and the law of refraction, for situations in which light passes through matter.

Section Summary

- A straight line that originates at some point is called a ray.

- The part of optics dealing with the ray aspect of light is called geometric optics.

- Light can travel in three ways from a source to another location: (1) directly from the source through empty space; (2) through various media; (3) after being reflected from a mirror.

In geometric optics, we will use a lot of, well, geometry. Here are a few problems to help you review the needed geometric concepts. If you need some review, have a look at:

- OpenStax Pre-algebra – Section 9.3: Use Properties of Angles, Triangles, and the Pythagorean Theorem.

- OpenStax Pre-algebra – Section 9.4: Properties of Rectangles, Triangles, and Trapezoids.

Problem 3: In geometric optics, we do analyses using similar triangles. This problem is here to help you practice working on these again.

Problem 4: Look at this map and determine the angle.

Problem 5: For this set of intersecting lines, use the following information to find the missing values.

The Law of Reflection

Whenever we look into a mirror, or squint at sunlight glinting from a lake, we are seeing a reflection. When you look at the page of a printed book, you are also seeing light reflected from it. Large telescopes use reflection to form an image of stars and other astronomical objects.

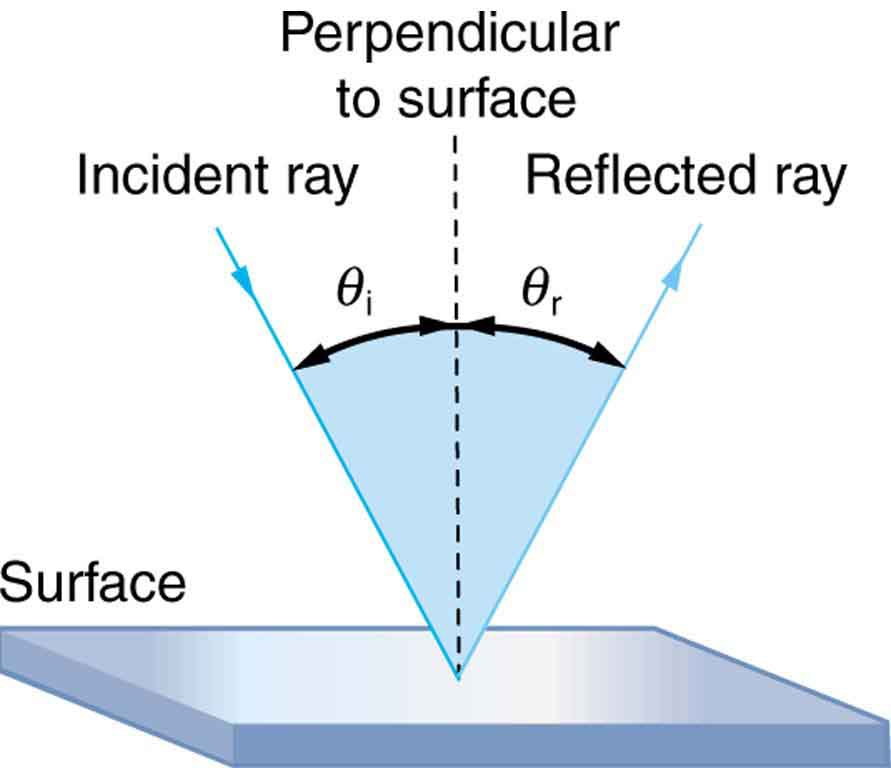

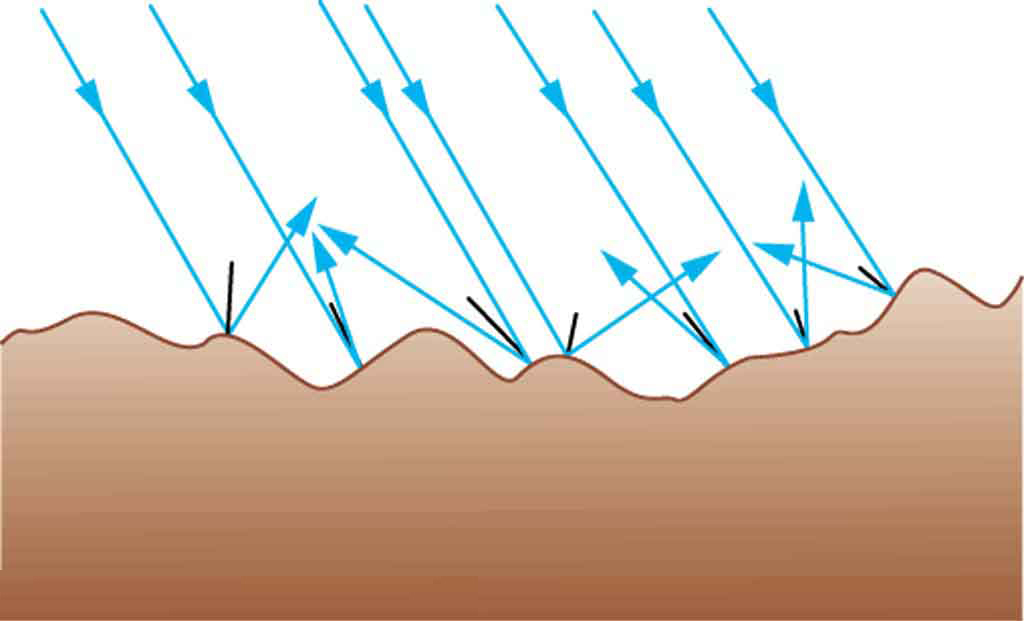

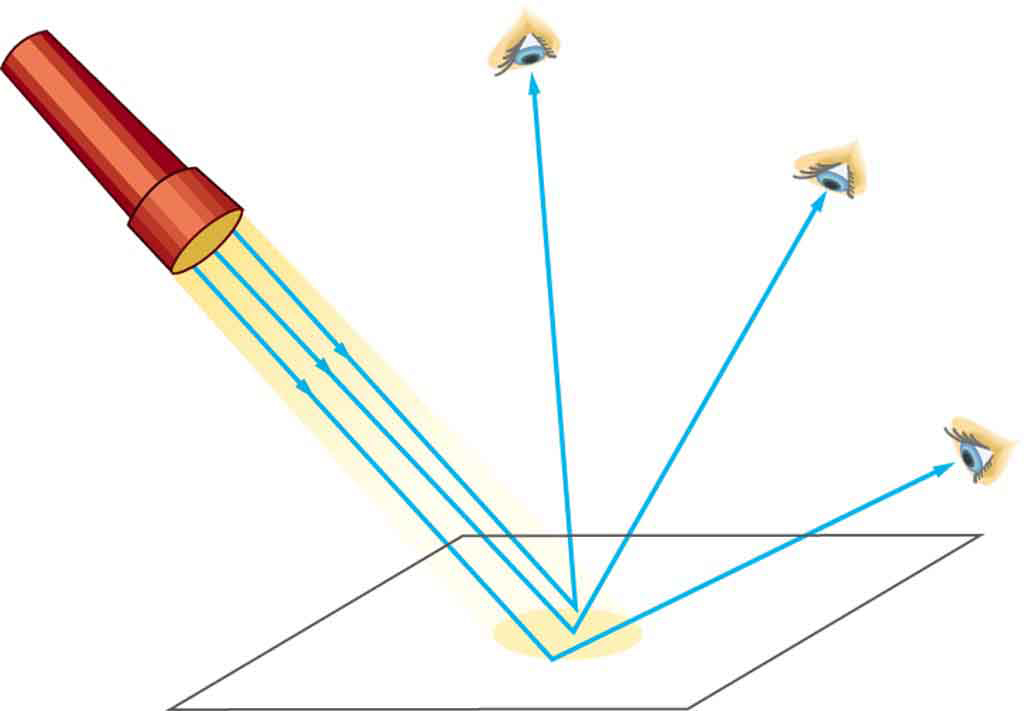

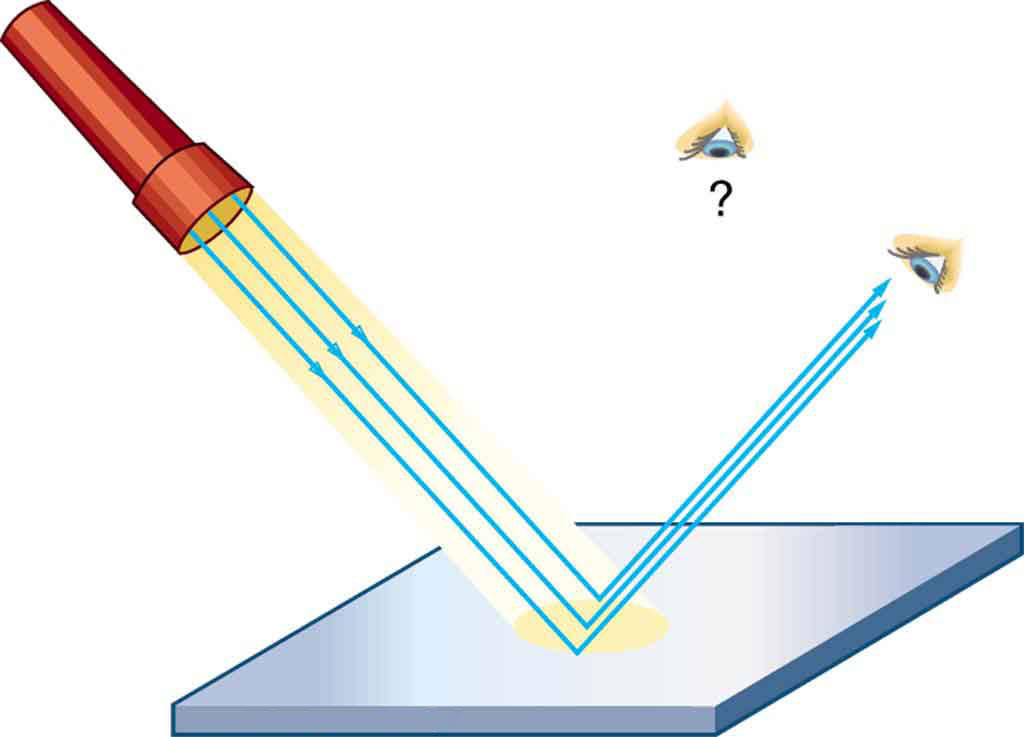

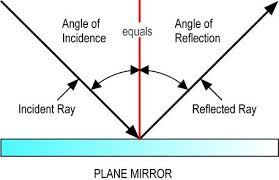

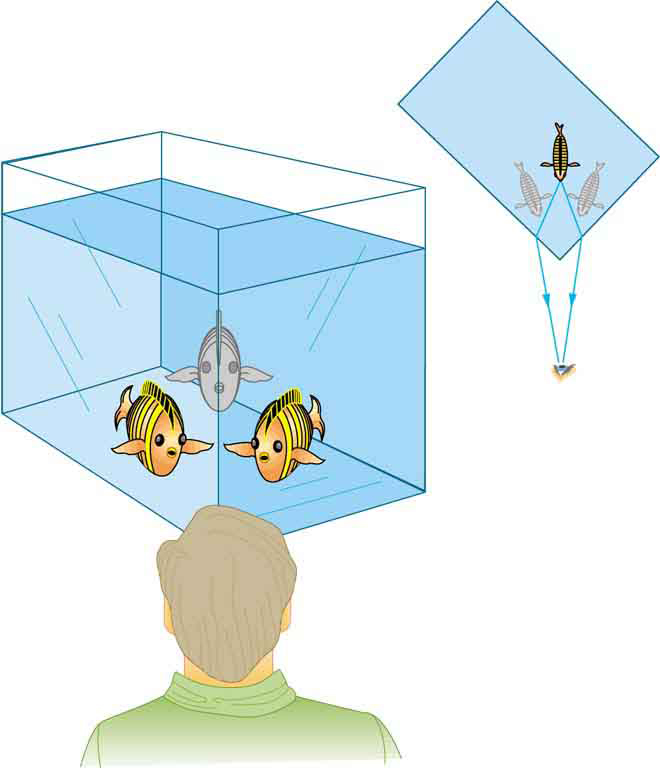

The law of reflection is illustrated in Figure 1, which also shows how the angles are measured relative to the perpendicular to the surface at the point where the light ray strikes. We expect to see reflections from smooth surfaces, but Figure 1 illustrates how a rough surface reflects light. Since the light strikes different parts of the surface at different angles, it is reflected in many different directions, or diffused. Diffused light is what allows us to see a sheet of paper from any angle, as illustrated in Figure 1. Many objects, such as people, clothing, leaves, and walls, have rough surfaces and can be seen from all sides. A mirror, on the other hand, has a smooth surface (compared with the wavelength of light) and reflects light at specific angles, as illustrated in Figure 1. When the moon reflects from a lake, as shown in Figure 1, a combination of these effects takes place.

The law of reflection is very simple: The angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence.

THE LAW OF REFLECTION

The angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence.

Instructor’s Note

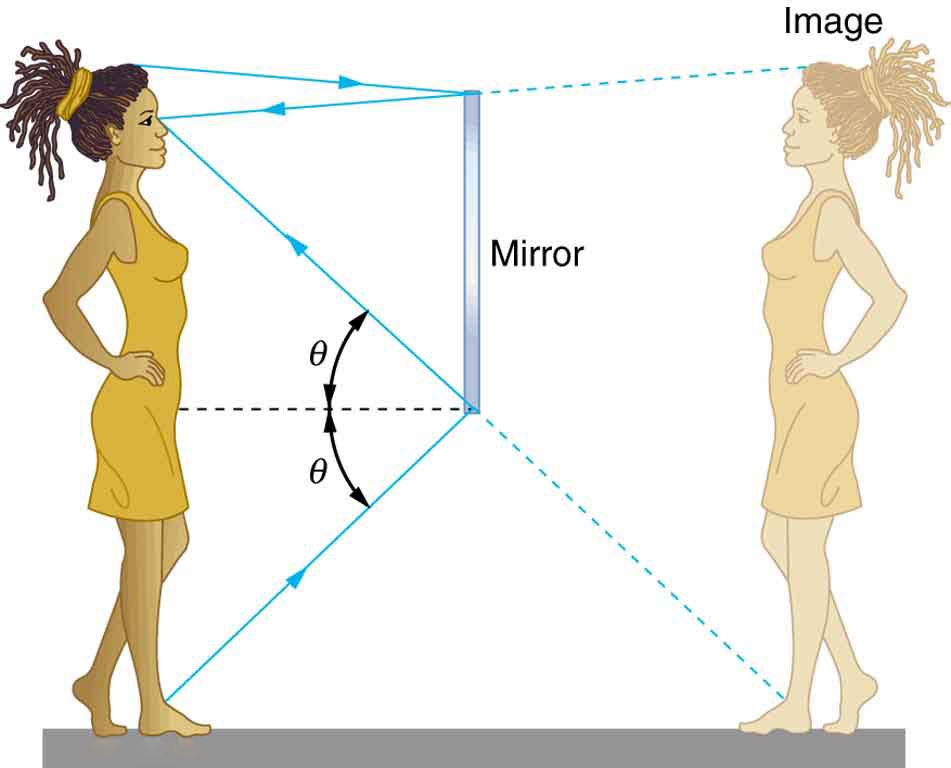

When we see ourselves in a mirror, it appears that our image is actually behind the mirror. This is illustrated in Figure 6. We see the light coming from a direction determined by the law of reflection. The angles are such that our image is exactly the same distance behind the mirror as we stand away from the mirror. If the mirror is on the wall of a room, the images in it are all behind the mirror, which can make the room seem bigger. Although these mirror images make objects appear to be where they cannot be (like behind a solid wall), the images are not figments of our imagination. Mirror images can be photographed and videotaped by instruments and look just as they do with our eyes (optical instruments themselves). The precise manner in which images are formed by mirrors and lenses will be treated in Applications of Geometric Optics: Terminology of Images.

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: LAW OF REFLECTION

Take a piece of paper and shine a flashlight at an angle at the paper, as shown in Figure 3. Now shine the flashlight at a mirror at an angle. Do your observations confirm the predictions in Figure 3 and Figure 4? Shine the flashlight on various surfaces and determine whether the reflected light is diffuse or not. You can choose a shiny metallic lid of a pot or your skin. Using the mirror and flashlight, can you confirm the law of reflection? You will need to draw lines on a piece of paper showing the incident and reflected rays. (This part works even better if you use a laser pencil.)

Section Summary

- The angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence.

- A mirror has a smooth surface and reflects light at specific angles.

- Light is diffused when it reflects from a rough surface.

- Mirror images can be photographed and videotaped by instruments

Problem 6: Indicate where the outgoing ray from a mirror intersects the dotted line.

Law of Reflection in Terms of the Particle Picture of Light

We’re going to begin with the basics of reflection. The Law of Reflection is simply, [latex]\theta_i = \theta_f[/latex] , the incident angle equals the final angle. Reflection makes the most sense in terms of the particle picture of light. It’s easiest to see if we just imagine light, a photon, as a ball. When a ball is bounced, the incident angle and the final angle are the same before and after it bounces. You can see that relative to the normal, which is how you should always measure your angles, the incident angle and the final angle are the same.

Speed of Light in Materials

REFRACTION

The changing of a light ray’s direction (loosely called bending) when it passes through variations in matter is called refraction.

Why does light change direction when passing from one material (medium) to another? It is because light changes speed when going from one material to another. So before we study the law of refraction, it is useful to discuss the speed of light and how it varies in different media.

The Speed of Light

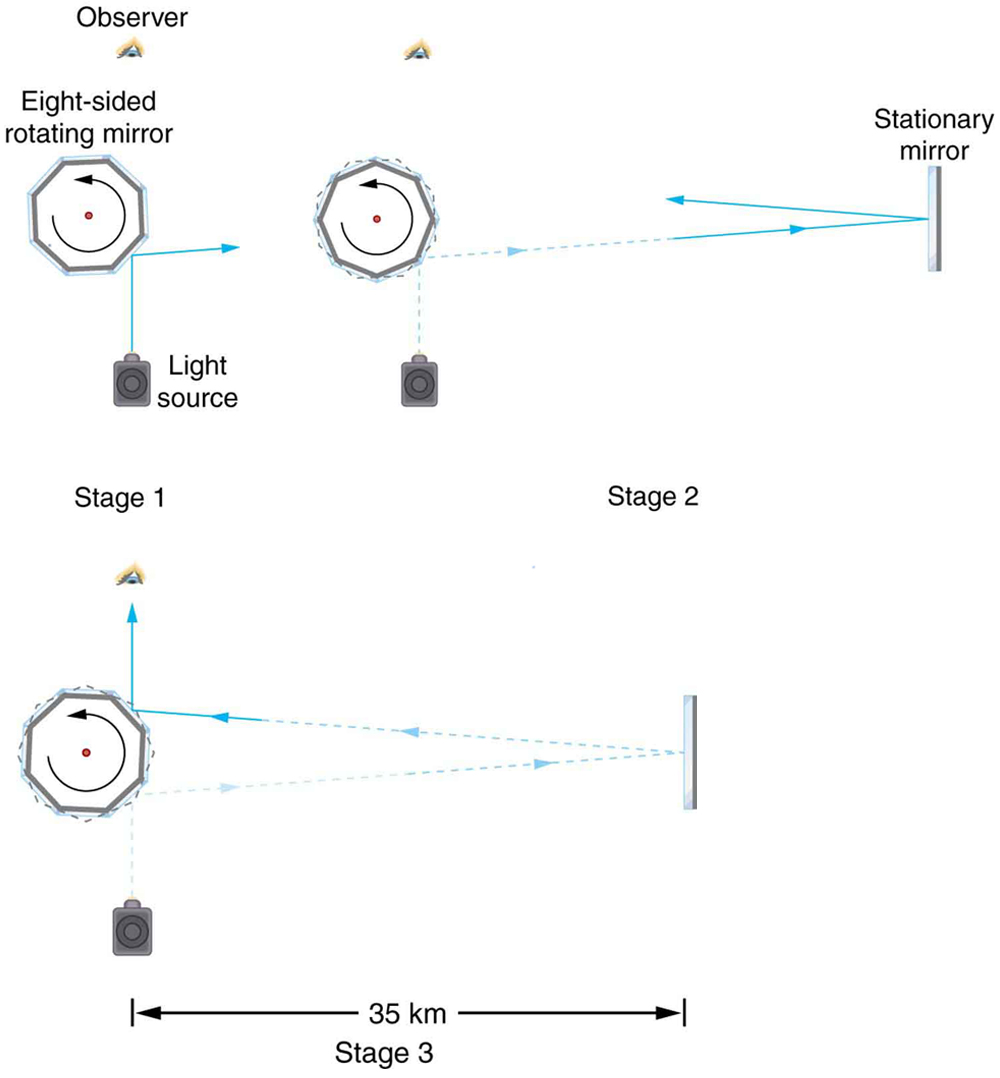

Early attempts to measure the speed of light, such as those made by Galileo, determined that light moved extremely fast, perhaps instantaneously. The first real evidence that light traveled at a finite speed came from the Danish astronomer Ole Roemer in the late 17th century. Roemer had noted that the average orbital period of one of Jupiter’s moons, as measured from Earth, varied depending on whether Earth was moving toward or away from Jupiter. He correctly concluded that the apparent change in period was due to the change in distance between Earth and Jupiter and the time it took light to travel this distance. From his 1676 data, a value of the speed of light was calculated to be [latex]2.26 \times 10^{8} m/s[/latex] (only 25% different than today’s accepted value). In more recent times, physicists have measured the speed of light in numerous ways and with increasing accuracy. One particularly direct method, used in 1887 by the American physicist Albert Michelson (1852–1931), is illustrated in Figure 2. Light reflected from a rotating set of mirrors was reflected from a stationary mirror 35 km away and returned to the rotating mirrors. The time for the light to travel can be determined by how fast the mirrors must rotate for the light to be returned to the observer’s eye.

The speed of light is now known to great precision. In fact, the speed of light in a vacuum, [latex]c[/latex], is so important that it is accepted as one of the basic physical quantities and has the fixed value.

[latex]2.99792458 \times 10^{8} m/s \approx 3.0 \times 10^{8} m/s[/latex],

where the approximate value of [latex] 3.0 \times 10^{8} m/s[/latex] is used whenever three-digit accuracy is sufficient. The speed of light through matter is less than it is in a vacuum, because light interacts with atoms in a material. The speed of light depends strongly on the type of material, since its interaction with different atoms, crystal lattices, and other substructures varies. We define theindex of refraction [latex]n[/latex] of a material to be

[latex]n = \frac {c}{v}[/latex],

where[latex]v[/latex] is the observed speed of light in the material. Since the speed of light is always less than[latex]c[/latex] in matter and equals [latex]c[/latex] only in a vacuum, the index of refraction is always greater than or equal to one.

VALUE OF THE SPEED OF LIGHT

[latex]2.99792458 \times 10^{8} m/s \approx 3.0 \times 10^{8} m/s[/latex]

INDEX OF REFRACTION

[latex]n = \frac {c}{v}[/latex]

That is, [latex]n \ge 1[/latex] Table 1 gives the indices of refraction for some representative substances. The values are listed for a particular wavelength of light, because they vary slightly with wavelength. (This can have important effects, such as colors produced by a prism.) Note that for gases, [latex]n[/latex] is close to 1.0. This seems reasonable, since atoms in gases are widely separated and light travels at[latex]c[/latex] in the vacuum between atoms. It is common to take[latex]n = 1[/latex]for gases unless great precision is needed. Although the speed of light [latex]v[/latex] in a medium varies considerably from its value[latex]c[/latex]in a vacuum, it is still a large speed.

| Index of refraction in Various Media |

|

| Medium | [latex]n[/latex] |

| Gases at [latex]0^{\circ} C , 1 atm[/latex] | |

| Air | 1.000293 |

| Carbon Dioxide | 1.00045 |

| Hydrogen | 1.000139 |

| Oxygen | 1.000271 |

| Liquids at [latex]20^{\circ} C[/latex] | |

| Benzene | 1.501 |

| Carbon disulfide | 1.628 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 1.461 |

| Ethanol | 1.361 |

| Glycerine | 1.473 |

| Water, fresh | 1.333 |

| Solids at [latex]20^{\circ} C[/latex] | |

| Diamond | 2.419 |

| Fluorite | 1.434 |

| Glass, crown | 1.52 |

| Glass, flint | 1.66 |

| Ice at [latex]20 ^{\circ}C[/latex] | 1.309 |

| Polystyrene | 1.49 |

| Plexiglass | 1.51 |

| Quartz, crystalline | 1.544 |

| Quartz, fused | 1.458 |

| Sodium chloride | 1.544 |

| Zircon | 1.923 |

Speed of Light in Matter

Calculate the speed of light in zircon, a material used in jewelry to imitate diamond.

Strategy

The speed of light in a material, [latex]v[/latex], can be calculated from the index of refraction [latex]n[/latex] of the material using the equation [latex]n = \frac {c}{v}[/latex]

Solution

The equation for index of refraction states that [latex]n = \frac {c}{v}[/latex], Rearranging this to determine [latex]v[/latex] gives

[latex]v = \frac {c}{n}[/latex]

The index of refraction for zircon is given as 1.923 in Table 1, and [latex]c[/latex] is given in the equation for speed of light. Entering these values in the last expression gives

Discussion

This speed is slightly larger than half the speed of light in a vacuum and is still high compared with speeds we normally experience. The only substance listed in Table 1 that has a greater index of refraction than zircon is diamond. We shall see later that the large index of refraction for zircon makes it sparkle more than glass, but less than diamond.

Section Summary

- The changing of a light ray’s direction when it passes through variations in matter is called refraction.

- The speed of light in vacuum [latex]2.99792458 \times 10^{8} m/s \approx 3.0 \times 10^{8} m/s[/latex]

- Index of refraction [latex]n = \frac {c}{v}[/latex], where [latex]v[/latex] the speed of light in the material, [latex]c[/latex] is the speed of light in vacuum, and [latex]n[/latex] is the index of refraction.

Problem 7: What is the speed of light in water? In glycerine? The indices of refraction for water is 1.333 and for glycerine is 1.473.

Problem 8: Calculate the index of refraction for a medium in which the speed of light is 1.416×108 m/s.

Why Light Bends

A wave is a wave is a wave

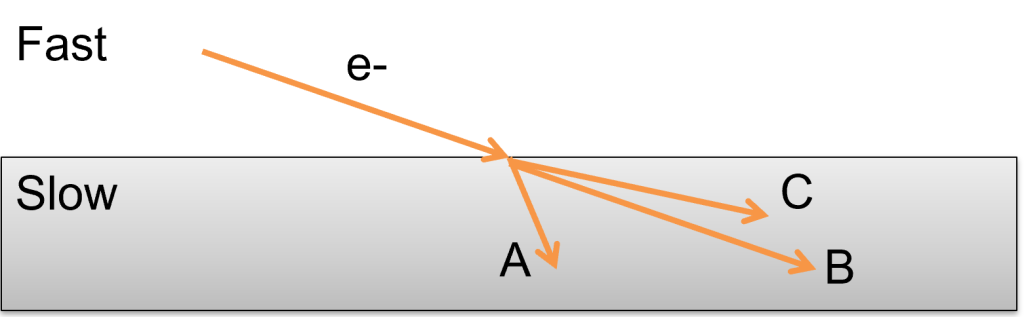

We have seen in our first unit that electrons and photons are similar in many ways; “a wave is a wave is a wave.” With that in mind, consider the following situation. An electron is traveling in some region when it enters another region where it travels more slowly (perhaps because of more potential energy and thus a decrease in kinetic energy). Which path of the electron is qualitatively correct?

Solution:

A is correct.

Wave hitting interface perpendicular

If the wave comes in straight perpendicular, does it bend?

Solution:

Digging More into Wave-Particle Duality and Refraction[1]

Now, let’s think about some of the other properties of the light wave, beyond speed, and how they might change as we go from one material to another. Starting with wavelength.

Wavelength

We know from Unit I that light is made of photons and that these photons have energy

[latex]E_\gamma = \frac{hc}{\lambda}[/latex].

The [latex]c[/latex] in this equation, however, is trying to tell us something. The value [latex]c = 3 \times 10^8 \, \mathrm{m}{s}[/latex] is the speed of light in vacuum. We know now that, in a material, light will slow to some [latex]v < c[/latex], and our resulting expression will now be

[latex]E_\gamma^{\mathrm{material}} = \frac{hv}{\lambda}[/latex]

where [latex]v[/latex] is the speed of the light in the material. Because of conservation of energy, the energy of the photon cannot change. Thus, according to our equation, if the speed goes down, the wavelength must also decrease by the same factor.

Example: Reduction of wavelength in materials

Say we have a light source in a vacuum that emits light with a wavelength of [latex]\lambda_0 = 6 \, \mathrm{nm} = 6 \times 10^{-9} \, \mathrm{m}[/latex]. The light then enters a material where the speed of light is only [latex]2 \times 10^{8} \, \mathrm{m}/\mathrm{s}[/latex]. What is the wavelength [latex]\lambda_n[/latex] in this new material?

Solution:

Given that

[latex]E_\gamma^{\mathrm{vacuum}} = \frac{hc}{\lambda_0}[/latex]

and

[latex]E_\gamma^{\mathrm{material}} = \frac{hv}{\lambda_n}[/latex]

and given he energy of the photon cannot change due to conservation of energy:

[latex]E_\gamma^{\mathrm{vacuum}} = E_\gamma^{\mathrm{material}}[/latex]

we can set the two expressions equal to another:

[latex]\frac{hc}{\lambda_0} = \frac{hv}{\lambda_n}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{c}{\lambda_0} = \frac{v}{\lambda_n}[/latex]

[latex]\frac{c}{v} = \frac{\lambda_0}{\lambda_n}[/latex].

We recognize the quantity [latex]c/v[/latex] as the index of refraction [latex]n = c/v[/latex], which in this case is

[latex]n = \frac{c}{v} = \frac{3 \times 10^8 \, \mathrm{m/s}}{2 \times 10^8 \, \mathrm{m/s}} = 1.5[/latex]

Thus, we have

[latex]n = \frac{\lambda_0}{\lambda_n}[/latex]

[latex]\lambda_n = \frac{\lambda_0}{n}[/latex]

Substituting in our values, we have:

[latex]\lambda_n = \frac{6 \, \mathrm{nm}}{1.5} = 4 \, \mathrm{nm}[/latex].

Discussion:

The speed of light went down by a factor of 2/3 and so did the wavelength!

Frequency

What happens to the frequency of a light wave in matter? Well the fundamental relationship for all waves [latex]v = \lambda \nu[/latex] must still be obeyed. As a light wave goes from a vacuum into a material, the speed changes [latex]c \rightarrow v = c/n[/latex], and so does the wavelength [latex]\lambda_0 \rightarrow \lambda_n = \lambda_0/n[/latex]. What happens to the frequency?

[latex]v = \lambda_n \nu[/latex]

[latex]\Downarrow[/latex]

[latex]\frac{c}{n} = \frac{\lambda_0}{n} \nu[/latex]

cancel the [latex]n[/latex] and we are left with the true statement [latex]c = \lambda_0 \nu[/latex]. What to make of this? It means that the frequency of the light wave does not change!

Amplitude / Number of Photons

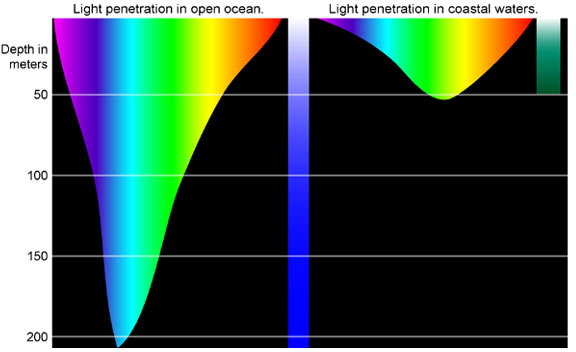

As you know from Unit I, the amplitude of the light wave and the number of photons are both related to the light’s intensity. Thus, these quantities are more about how much light is absorbed by the material than its index of refraction. Glass and air absorb very little light in the visible range, meaning that the amplitude and number of photons is not very much reduced in these materials. Water on the other hand, is very effective at absorbing visible light photons. As shown in the Figure, at a depth of 200m, almost no visible light penetrates resulting in creatures with special adaptations to live in complete darkness.

Problem 10: Which of the properties of a light ray change as it goes from glass to vacuum?

Problem 11: What are the wavelengths of visible light in crown glass?

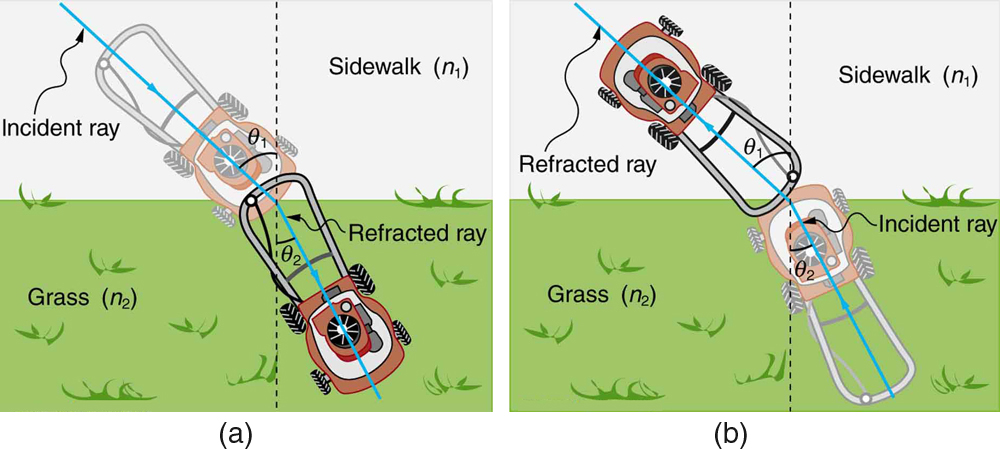

The Law of Refraction

Figure 1 shows how a ray of light changes direction when it passes from one medium to another. As before, the angles are measured relative to a perpendicular to the surface at the point where the light ray crosses it. (Some of the incident light will be reflected from the surface, but for now we will concentrate on the light that is transmitted.) The change in direction of the light ray depends on how the speed of light changes. The change in the speed of light is related to the indices of refraction of the media involved. In the situations shown in Figure 1, medium 2 has a greater index of refraction than medium 1. This means that the speed of light is less in medium 2 than in medium 1. Note that as shown in Figure 1 (a), the direction of the ray moves closer to the perpendicular when it slows down. Conversely, as shown in Figure 1 (b), the direction of the ray moves away from the perpendicular when it speeds up. The path is exactly reversible. In both cases, you can imagine what happens by thinking about pushing a lawn mower from a footpath onto grass, and vice versa. Going from the footpath to grass, the front wheels are slowed and pulled to the side as shown. This is the same change in direction as for light when it goes from a fast medium to a slow one. When going from the grass to the footpath, the front wheels can move faster and the mower changes direction as shown. This, too, is the same change in direction as for light going from slow to fast.

The amount that a light ray changes its direction depends both on the incident angle and the amount that the speed changes. For a ray at a given incident angle, a large change in speed causes a large change in direction, and thus a large change in angle. The exact mathematical relationship is the law of reflection, or “Snell’s Law,” which is stated in equation form

[latex]n_1 \sin \theta_1 = n_2 \sin \theta_2[/latex]

Here [latex]n_1[/latex] and [latex]n_2[/latex] are the indices of refraction for medium 1 and 2, and [latex]\theta_1[/latex] and [latex]\theta_2[/latex] are the angles between the rays and the perpendicular in medium 1 and 2, as shown in Figure 1. The incoming ray is called the incident ray and the outgoing ray the refracted ray, and the associated angles the incident angle and the refracted angle. The law of refraction is also called Snell’s law after the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell (1591–1626), who discovered it in 1621. Snell’s experiments showed that the law of refraction was obeyed and that a characteristic index of refraction [latex]n[/latex] could be assigned to a given medium. Snell was not aware that the speed of light varied in different media, but through experiments he was able to determine indices of refraction from the way light rays changed direction. Below is a simulation where you can shine light through different materials and see how it bends. I encourage you to play with it to get a feel for refraction. You can even add a protractor and see that the simulation obeys Snell’s Law.

THE LAW OF REFRACTION

[latex]n_1 \sin \theta_1 = n_2 \sin \theta_2[/latex]

TAKE-HOME EXPERIMENT: A BROKEN PENCIL

A classic observation of refraction occurs when a pencil is placed in a glass half filled with water. Do this and observe the shape of the pencil when you look at the pencil sideways, that is, through air, glass, water. Explain your observations. Draw ray diagrams for the situation.

Determine the Index of Refraction form Refraction Data

Find the index of refraction for medium 2 in Figure 1 (a), assuming medium 1 is air and given the incident angle is [latex]30^{\circ}[/latex] and the angle of refraction is [latex]22^{\circ}[/latex]

Strategy

The index of reflection for air is taken to be 1 in most cases (and up to four significant figures, it is 1.00). Thus [latex]n_1 = 1.00[/latex]. Form the given information, [latex]\theta_1 = 30^{\circ}[/latex] and [latex]\theta_2 = 22^{\circ}[/latex]. With this information, the only unknown in Snell’s law is [latex]n_2[/latex], so it can be used to find this unknown.

Solution

Snell’s law is

[latex]n_1 \sin \theta_1 = n_2 \sin \theta_2[/latex]

Rearranging to isolate [latex]n_2[/latex] gives

[latex]n_2 = n_1 \frac{\sin \theta_1} {\sin \theta_2}[/latex]

Entering known values,

[latex]n_2 = 1.00 \frac{\sin 30.0^{\circ}} {\sin 22 .0^{\circ}} = \frac{0.500}{0.375}[/latex]

[latex]n_2 = 1.33 [/latex]

Discussion

This is the index of refraction for water, and Snell could have determined it by measuring the angles and performing this calculation. He would then have found 1.33 to be the appropriate index of refraction for water in all other situations, such as when a ray passes from water to glass. Today we can verify that the index of refraction is related to the speed of light in a medium by measuring that speed directly.

A Larger Change in Direction

Find the index of refraction for medium 2 in Figure 1 (a), assuming medium 1 is air and given the incident angle is [latex]30^{\circ}[/latex] and the angle of refraction is [latex]22^{\circ}[/latex]

Strategy

Again the index of refraction for air is taken to be [latex]n_1 = 1.00[/latex] and we are given [latex]\theta_1 = 30^{\circ}[/latex]. We can look up the index of refraction for a diamond in Table 1 (Speed of Light in Materials), finding [latex]n_2 = 2.419[/latex]. The only unknown in Snell’s law is [latex]\theta_2[/latex], which we wish to determine.

Solution

Solving Snell’s law for [latex]\ sin \theta_2[/latex] yields

[latex]\ sin \theta_2 = \ sin \theta_1 \frac{n_1} { n_2}[/latex]

Entering known values,

[latex]\ sin \theta_2 = \ sin 30^{\circ} \frac{1.00} {2.419} = (0.413) (0.500) = 0.207[/latex]

And angle is thus

[latex]\theta_2 = \sin^{-1} 0.207 = 11.9^{\circ} [/latex]

Discussion

This is the index of refraction for water, and Snell could have determined it by measuring the angles and performing this calculation. He would then have found 1.33 to be the appropriate index of refraction for water in all other situations, such as when a ray passes from water to glass. Today we can verify that the index of refraction is related to the speed of light in a medium by measuring that speed directly.

For the same [latex]30^{\circ}[/latex] angle of incidence, the angle of refraction in diamond is significantly smaller than in water ([latex]11.9^{\circ}[/latex] rather than [latex]22^{\circ}[/latex]—see the preceding example). This means there is a larger change in direction in diamond. The cause of a large change in direction is a large change in the index of refraction (or speed). In general, the larger the change in speed, the greater the effect on the direction of the ray.

Section Summary

- Snell’s law, the law of refraction, is stated in equation form as [latex]n_1 \theta_1 = n_2 \theta_2[/latex]

Problem 12: Suppose you have an unknown clear substance immersed in water, and you wish to identify it by finding its index of refraction. You arrange to have a beam of light enter it at an angle of 48.6∘, and you observe the angle of refraction to be 32.4∘. What is the index of refraction of the substance? Water has an index of refraction equal to 1.333.

Problem 13: A beam of white light goes from air into water at an incident angle of 83.0∘. At what angles are the red 660 nm and violet 410 nm parts of the light refracted? Red light in water has an index of refraction equal to 1.331 and that of violet light is 1.342.

Problem 14: Given that the angle between the ray in the water and the perpendicular to the water is 28.3∘, and using information in the figure above, find the height of the instructor’s head above the water. Water has an index of refraction equal to 1.333.

- A note to more advanced readers - the following derivation of why the wavelength changes and not the frequency is not 100% correct, there are more complex effects at play due to Einstein's Theories of Relativity. However, the essence of the argument depending on energy conservation is correct and so is the result. ↵

A smooth surface that reflects light at specific angles, forming an image of the person or object in front of it

The angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence.

for a material, the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to that in the material [latex]n = c/v[/latex]. Always greater than 1.

Power per area:

I = P/A

or, using P = E/t,

I = E/(At)

Incoming ray

A ray that has been bent by a refraction, such as in a lens.